Guest Report by Benjamin Skolnik,

Conservation Projects Specialist, American Bird Conservancy

It takes people to achieve on-the-ground conservation. This simple observation is actually quite complex given the variety of threatened ecosystems and our enormous and diverse human population, particularly in Latin America.

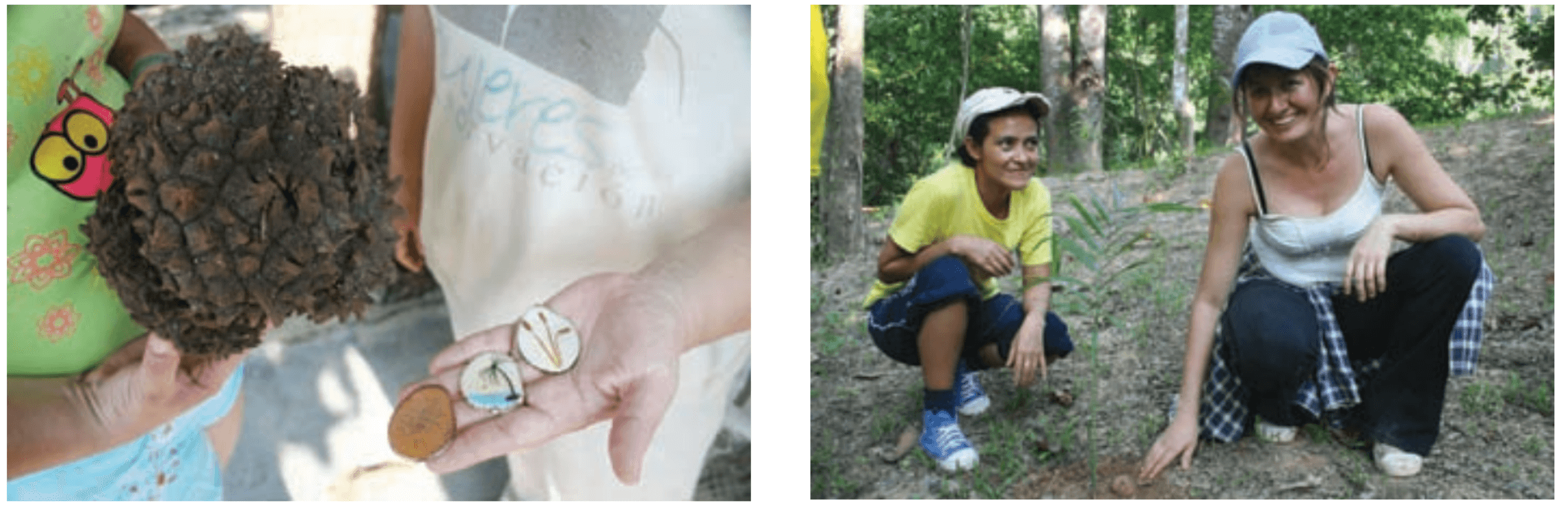

Earlier this year, I found myself racing to keep up with a group of local women in the tropical forests of central Colombia, experiencing first-hand the complexity and beauty of this relationship between conservation and people. Gloria, the unofficial leader of the group, turned sharply off the trail, and descended nimbly into the thick vegetation. She must have spotted the characteristic palm leaves from above. As I slid along down the hill to catch up, Gloria already held two handfuls of oval, chocolate-colored tagua seeds. She filled her satchel and turned to move on down the ravine to meet up with the others to see how many seeds they had collected.

These seeds are the raw material used to create tagua jewelry that, since 2004, has enabled a dozen women from a small town in the Magdalena Valley to forge new lives and achieve an independent and sustainable source of income by producing jewelry and other crafts from natural products of the forest. In recent years, the Colombian war on drugs has significantly curbed the coca industry. Despite the obvious benefits, one of the unintended consequence of this effort is that many people, particularly women, have been left without a viable source of income. The result has been increasing pressure on local forests for food and timber, prompting ProAves, Women for Conservation, and American Bird Conservancy to team up with the World Land Trust to purchase land.

This Women for Conservation program was begun in an attempt to connect people’s livelihoods to the environment and make the benefits of the reserve more tangible with sustainable use of forest products. ProAves began a pilot program in 2004 that employed women to make high-quality handicrafts including tagua jewelry that are then sold locally, nationally, and internationally. Their products include bracelets, earrings, necklaces, bookends, bookmarks, paper, hats, wallets, belts, and shoes.

Six years later, the venture has expanded to four reserves in Colombia and employs 48 women full-time. The women have tapped into various markets, and have recently begun to provide soap and candles to the tourist lodges on ProAves reserves. A signed contract ensures the commitment of the women and their families to the program and their support of conservation at the reserve.

Andrea Linares coordinates the project for ProAves and feels that her job “is not work, but a way of life” because teaching women to be productive and self-confident is extremely fulfilling. As one woman commented, the production of artisan crafts “is the best opportunity to express ourselves as women”. Many of these women have bleak histories of poverty and hunger, and the project has inspired new-found confidence in them. One woman is now able to afford food and clothing for her child, who was previously living with her grandmother. The project is also having a lasting effect by building a coalition of inspired conservationists for the future.

The seeds are now a much sought-after commodity, and I am excited to be part of this collecting foray. The women fill large sacks with the heavy seeds, most of which are scavenged from the ground. We take them back to town and, using a hammer, crack the extremely tough seed casing to extract the tagua itself. Each seed is the size of a child’s fist and seems as hard as ivory. The women will send them off to the city to be thinly sliced and sanded down. Andrea has taught them how to paint, polish, and string the pieces into fine jewelry. Such crafts are growing in popularity and the market for tagua jewelry has exploded throughout Latin America. Once a renewable resource, the palm seeds sometimes never have a chance to grow to maturity as people harvest all the seeds from forests. The women here are conscious of this, and we spend the afternoon planting some of these seeds near the ecolodge so there will be tagua in coming years.

Tagua palms take twenty years to reach maturity, but the women seem happy to think of their daughters benefiting. The birds of Colombia will benefit too from this foresight, and the protection of reserves that is much more likely to persist long into the future thanks to this program.